OPENING MONOLOGUE

Hello there from Poland.

I scrapped the first draft of this week’s newsletter to address the passing of David Lynch.

Nes from Paraspaceot is the official newsletter for Christian A. Dumais — an American writer and editor living in Poland. NPR once said, "People get paid a LOT of money to write comedy who are not one-tenth as funny as [Christian]." Your mileage may vary.

This one is all about Lynch, so buckle up.

Today's reading

AT THE DESK

Everything is Dark

David Lynch died last week.

Like many Gen Xers, I discovered David Lynch when Twin Peaks aired on ABC in 1990. I knew his work though. The Elephant Man was an HBO staple in the 80s, and there was Dune, of course — I just didn’t know Lynch as a director or icon.

(Fun fact: When Dune came out in 1984, my uncle was visiting with his girlfriend Bubba. She promised to take my brother and me to see the movie, but we learned, like the rest of our family, not to trust a woman named Bubba.)

It’s hard to convey to those who weren’t there how huge Twin Peaks was. It wasn’t that the show was slightly different than mainstream TV — there was nothing like it on television. It was a seismic shift. It had a central mystery (“Who killed Laura Palmer?”) at the starting line that was usually reserved for season finales (ala “Who shot JR?”). And, most importantly, it was spooky, and funny, and fucking weird. And David Lynch’s name was all over it.

(I’m not trying to downplay Mark Frost’s involvement with Twin Peaks here. I think a lot of the magic of the series — especially with the third season — comes from how Lynch’s and Frost’s ideas collide. I could go on and on about their partnership, but today, I want to focus on Lynch.)

In the summer of 1990, I really discovered Lynch. I rented and watched Eraserhead and Blue Velvet and I was off to the races.

Though the extended second season of Twin Peaks couldn’t live up to the abbreviated first, I was still a huge fan of the show. Looking back, part of the miracle of that first season was that it was eight episodes long. Shifting it into a 22-episode a season show was a disservice. That said, even the show’s lowest points in the second season were more interesting than what you would find elsewhere on TV.

After Stephen King’s universe of books, the world of Twin Peaks is my favorite universe to daydream about. I love it so much.

My first real disappointment with Lynch was when he released Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me. I saw it with a group of my friends on opening night in 1992, and we just weren’t ready for it. I mean, how could we be? We were all in a daze when the lights came on. It was not how teenagers start a Friday night.

No one had ever done what Lynch did, turning the subject of a popular television show and turning it into the object of a movie. Fire Walk with Me is a two-hour-plus assault of the senses that seemingly punishes you for not taking into account the pain and suffering Laura Palmer experienced while we were busy trying to solve the mystery. Instead of asking, “Who killed Laura Palmer?” we should have been asking “Why Laura Palmer? Why anyone?”

This indictment wasn’t something a 17-year-old who was two weeks away from graduating high school could appreciate. I’d eventually come around to Fire Walk with Me. I think it’s a classic, and depending on my mood, I might even argue that it’s Lynch’s best work.

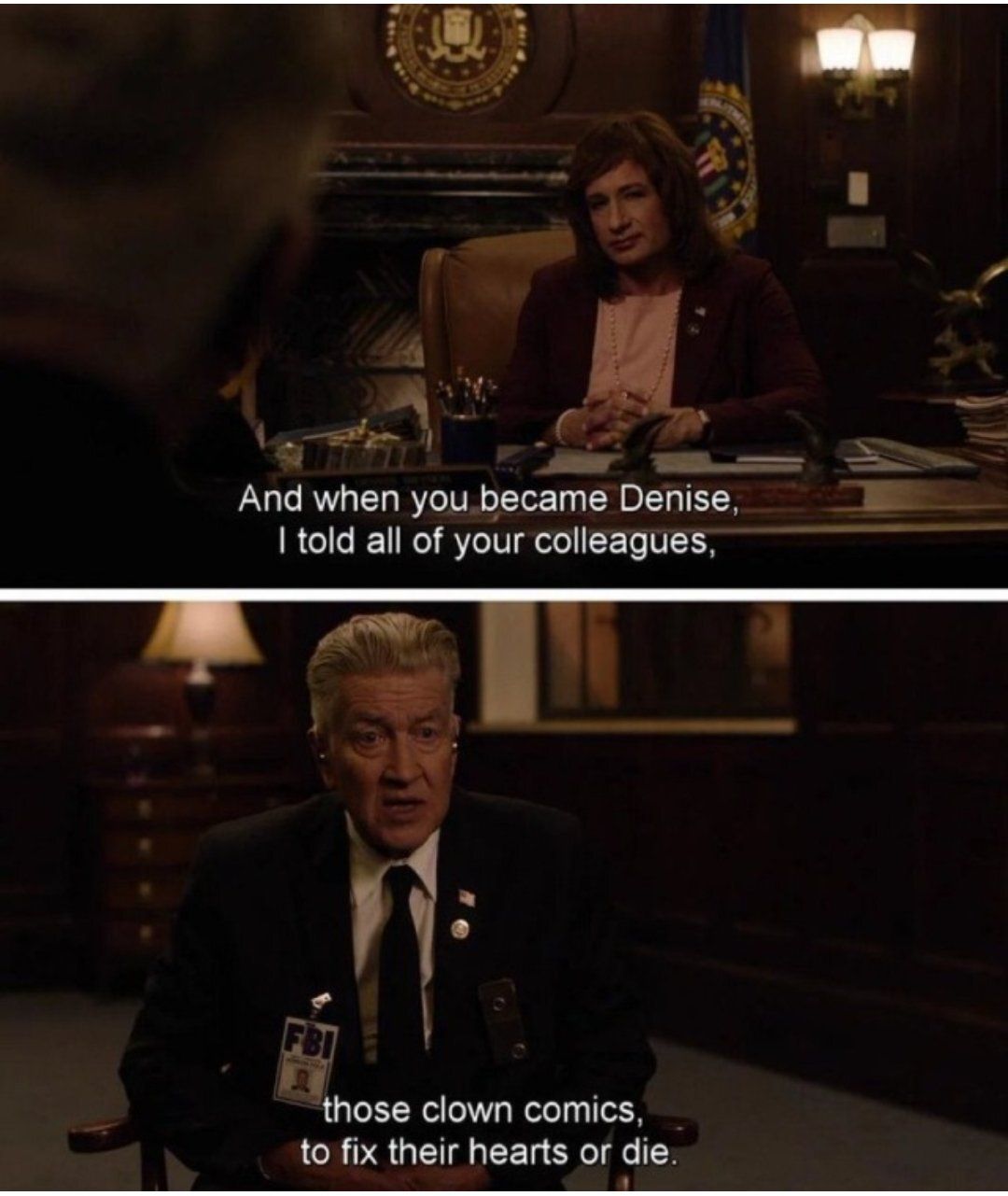

But most days, I think the best thing Lynch ever did was Twin Peaks: The Return (even better than Mullholland Drive, which I adore). I started my third re-watch on January 1st (as I write this, I’m at episode 16) and it’s insane how incredible it is. Very few creators have been able to return to their work decades later (in this case, 25 years) and pull off something this momentous. It’s not just restarting where the TV show left off, it’s putting down puzzle pieces that fit perfectly to Fire Walk with Me. It’s a glorious tapestry of intricate design.

(Every month there’s another debate online about whether The Return should be considered an 18-hour movie or a television show, and I think it’s because it’s so good that both TV and movie fans want to own it. Personally, I think of it as a show, but I can see the argument for both sides.)

A lot of attention is given to Episode 8 of The Return, where the show…well, explodes. I don’t want to ruin it for people going in blind, but it opens up the whole mystery in a new way. One of the surprises in the third season is how the story zooms out internationally, with moments all across the US and France (kind of). It’s as if to say that the rot that has been destroying the small town of Twin Peaks has been spreading. That the murder of a small town high school student — all violence for that matter — causes ripples in ways that we can’t understand. And Episode 8 extends this idea to pull back the curtain and reveal forces that were in play decades before Laura Palmer was born.

The thing that surprised me the most about The Return is how many questions it answers, how much closure it gives you. There’s a cathartic scene that brings two people together at the beginning of Episode 15 — something viewers have been waiting for since 1990 — that is an absolute joy to watch.

And that’s what makes Lynch so great. Even when he’s exploring long dark hallways, he opens some doors to reveal moments of laughter, love, or happiness, even if it’s fleeting. He knows it’s not all darkness, but there’s a lot of it. And the only thing to fight against this darkness is joy.

(This reminds me of how Stephen King uses deadlights in his stories. Take, for instance, this quote from his short story “Two Talented Bastids”: “Your world is a living breath in a universe that is mostly filled with deadlights.”)

I wish we got more of his work. But seeing the overwhelming amount of posts about Lynch on social media in the last few days, it’s clear he gave us more than enough.

I edited 1.5M words in 2024. I’m still blocking out time for my editing schedule in 2025. If you think I could be a worthy addition to your content team or I could be the right person for your manuscript, let’s talk.

READING LIST

Ideas, Space, and Fish

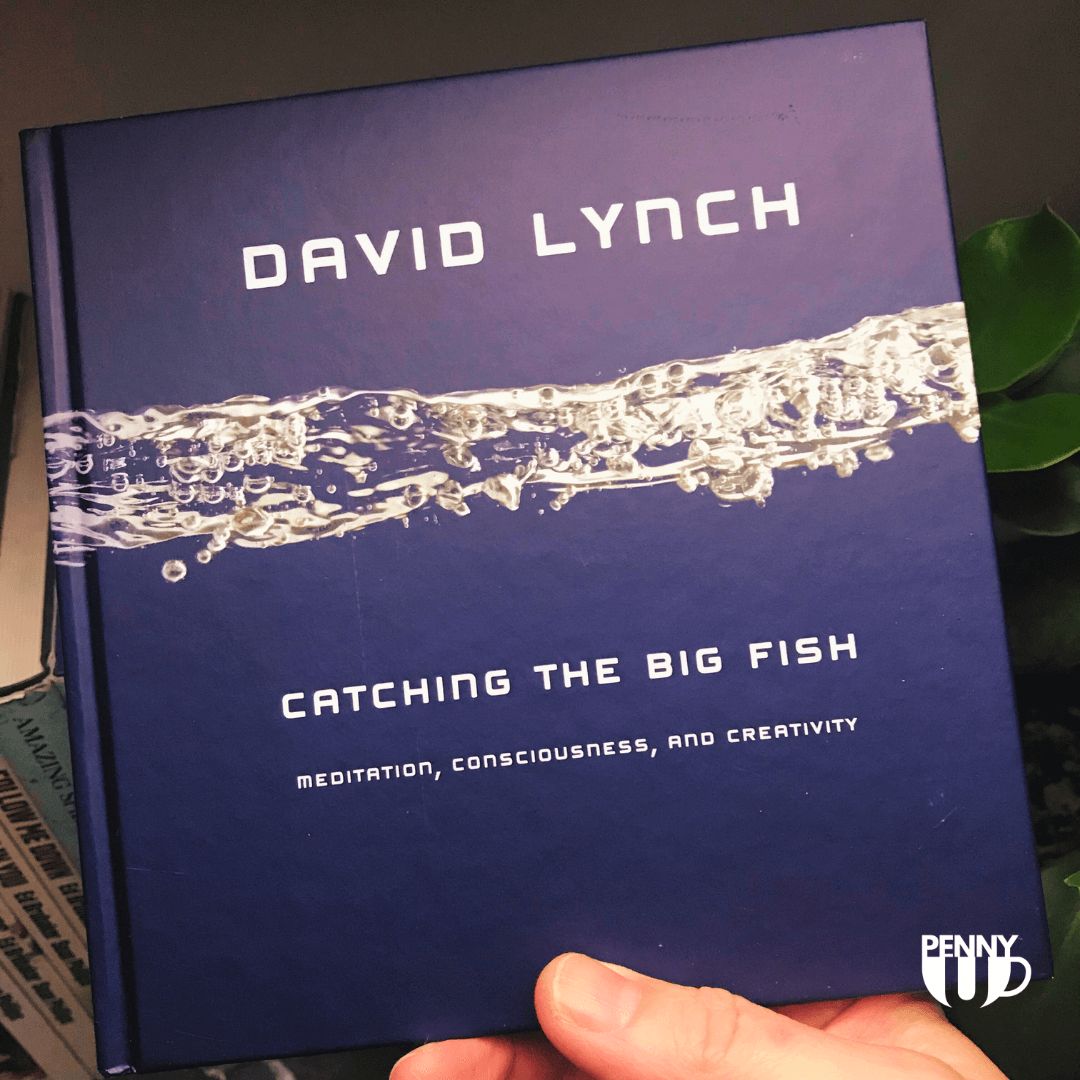

You might remember that I previously read Lynch’s Catching the Big Fish: Meditation, Consciousness, and Creativity:

This week’s palette cleanser was David Lynch’s Catching the Big Fish: Meditation, Consciousness, and Creativity. While delightful in its own right, your enjoyment of this book comes down to where you fall with Lynch. And maybe transcendental meditation, because it comes up a lot. If you’re looking for a quick boost of inspiration — especially in Lynch’s aw-shucks sort of way — then you’ll like this one, but if you’re looking for answers about Lynch’s work, you’ll walk away disappointed.

One of the things I loved about the book was this notion of ideas being something separate from us, that needed to be caught. In Lynch’s case, ideas are fish:

“Ideas are like fish. If you want to catch little fish, you can stay in the shallow water. But if you want to catch the big fish, you’ve got to go deeper. Down deep, the fish are more powerful and more pure. They’re huge and abstract. And they’re very beautiful.”

This brushes up against some (BIG) thoughts that comic book writer Grant Morrison has on the subject of ideas and imagination:

“I got the visionary experience like nothing I’d ever known before or since. I was taken out of Four-D reality, shown the entire universe as a single object, shown the world as it is from outside, the viewpoint of the Supercontext . . . and it was profound. . . . It was something I’d been waiting for, what Crowley would call the conversation with the Holy Guardian Angel. It feels like a contact with a future self, or with a self that exists outside time and space, in what Australian aborigines would call Aljira, the Dreamtime. Platonic reality. Which again is our translation of a word that is much more complex than ‘Dreamtime.’ . . . There is something else going on beyond 11-bit consciousness—everyone who explores ‘magical’ consciousness reports the same experiences. Philip K. Dick obviously had the same kind of experience in 1974. Alan Moore’s obviously had the same experience, judging from his recent work. Robert Anton Wilson’s obviously had the same experience. Buddha. Christ. Carlos Castaneda. David Icke! All these people offer corroboration and their own metaphors for framing the same experience. If Philip K. Dick says it’s contact with a Vast And Living Intelligence System, if Alan Moore calls it Ideaspace, if Robert Anton Wilson says it’s Cosmic Tricksters from Sirius, maybe we should just start accepting that certain types of thinking lead to a shift in consciousness which offers human minds a more inclusive view of Time, Space and Mind.”

Which brings us to writer Alan Moore and his delightful concept of Ideaspace:

“If Ideaspace or something like it does exist, however, then one must suppose that actual ideas represent the equivalent of solid objects in terms of that space. An idea may be a pebble, a rock, a mountain or a whole continent in terms of its stature, but the important thing is that it exists, at least metaphysically, as a solid object in this mutually-accessible terrain of the mind that I'm describing, just as if it were a spar of granite jutting from a physical landscape. Thus, numerous different people, all ‘wandering’ in their minds, might conceivably stumble across the same idea almost at once, like separate hill-walkers all having happened upon the same distinctive landmark. One thing that became clear almost immediately is that if awareness were to be considered as a space, then it must have different rules governing its structure than those which pertain to ordinary physical space.”

To achieve any of this, the go-to for Lynch was TM. Some people need drugs to get there. But, really, all it takes is carving out the time to go dreamy.

SIGNING OFF

The Weather Report

That’s it for this week.

Stay warm wherever you are. And thanks for reading.